Central banks forced to intervene to limit the spread of the banking crisis - 20 march 2023

The crisis at the heart of US regional banks and the unusual circumstances of UBS’s takeover of Credit Suisse have led investors to seek refuge in government bonds. The major banks are much better capitalised than in 2008, but the porous nature of the financial system has forced central banks to intervene.

Six months after the first warning from British pension funds, the crisis happening at some US regional banks (including SVB) and the collapse of Credit Suisse leave no further doubt: Monetary tightening is beginning to take its toll on the weakest players in the system. Balance sheets have been affected by unrealised capital losses on bond markets since early 2022, and competition from money market funds makes life more difficult for US banks, which only offer interest at rates much lower than those offered by money markets.

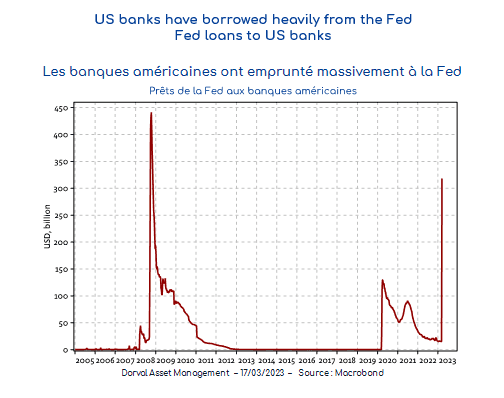

With the obvious exception of Credit Suisse, major US and European banks seem, a priori, safe from serious problems due to being much better capitalised than in 2007/2008. However, the porous nature of the financial system is making investors nervous. Thus, US banks flocked to use the liquidity window opened by the Fed, borrowing more than $300 billion from the central bank, a record high since 2008 (cf. chart 1).

Moreover, managing this type of crisis involves many players, including governments, which makes resolution scenarios more uncertain. This was evidenced by UBS’s takeover of Credit Suisse, which saw holders of AT1 subordinated bonds lose all their invested capital ($17 billion), while shareholders kept $6 billion paid by UBS. The European regulator has also reminded us that, usually, bondholders have priority over shareholders. In the United States, the bailout of regional banks is causing political reactions that could also weaken the coherence of the financial system’s safeguard plans.

This type of event tends to tighten financial conditions, which could cause the crisis to spread to sectors of the economy most dependent on these conditions, including real estate, venture capital and investment.

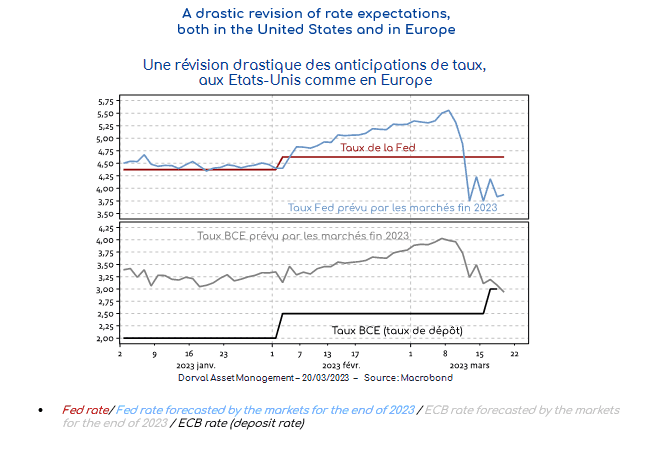

The current setbacks faced by some financial institutions – caused largely by the interest rate hikes of the major central banks – call for a sharp slowdown in or even a (temporary?) end to the monetary tightening process. The ECB continued to raise its rates last Thursday (+50 basis points), but the tone has changed. The central bank now includes the issue of financial stability in its communication. Markets no longer anticipate a rise in rates in Europe, and even forecast a sharp fall in rates in the United States (cf. chart 2). Revisions to these forecasts have been dramatic in recent days, with anticipated Fed rates for the end of the year dropping from over 5.5% on 8 March to below 4% today. The Fed monetary policy committee meets on Wednesday, 22 March.

These revisions are undoubtedly exaggerated, especially as the global economy remains dynamic with the upturn in China and easing of the energy crisis in Europe. In addition, even though investors’ fears are understandable, outflows have already been significant in the most sensitive market sectors (up to -25% for European banks, despite good profitability of the sector). As a precaution, however, we are taking a more cautious position in the short term in our most valuable funds.